Photo Credit: whisky.com

There’s plenty of discussion and debate over what makes a whisky smoky. After considerable research I have broken it down into four main categories with smoke as an umbrella term comprised of the following: peat; toasted barrel; charred barrel; bio-organic sulfuric molecular compounds, the byproducts of yeast fermentation.

The first source of smoke in whisky, and arguably the source with the most notariety is peat smoke. Peat is a fossil fuel used for heating in many parts of the world; it is also used for imbuing natural flavouring into whisky. This is accomplished by drying the barley for approximately 18 hours which causes the aromatic compounds in peat smoke to adhere to the barley. This drying time varies by distillery and varies by whisky depending on desired flavour profile. Generally speaking a longer drying time yields a higher part per million (ppm) of peat smoke particles having adhered to the barley, which is what will offer its unique peaty scent and flavour. Peat is not for the faint of heart. It’s boggy, but like opera or Baroque music once you’re turned onto it you cannot get enough of its undertone or even overtone. One thing to note about peat, what’s written on the bottle isn’t always what’s in the bottle; sometimes the ppm on the bottle expresses what was on the drying floor. Regardless, one can expect the higher the ppm the more peat presence will be in the final product.

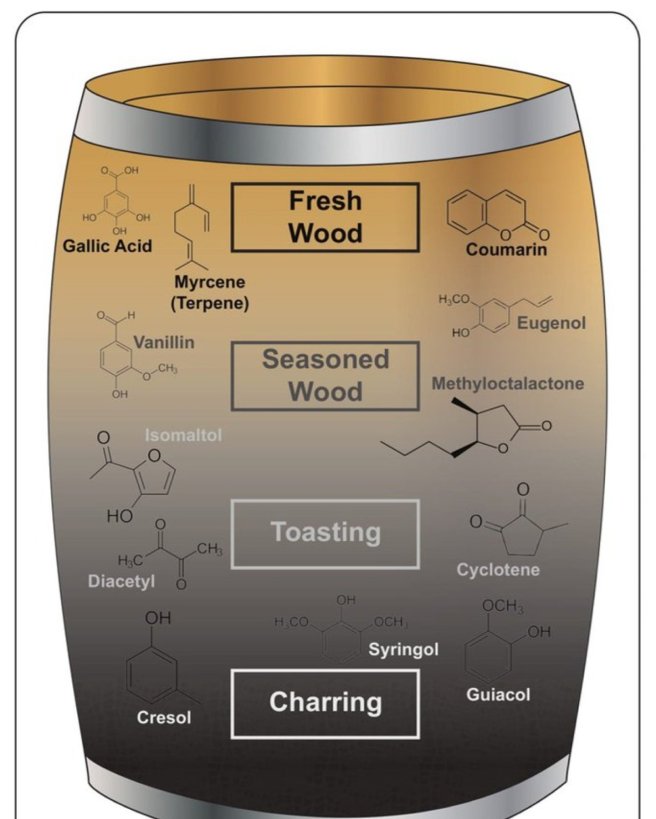

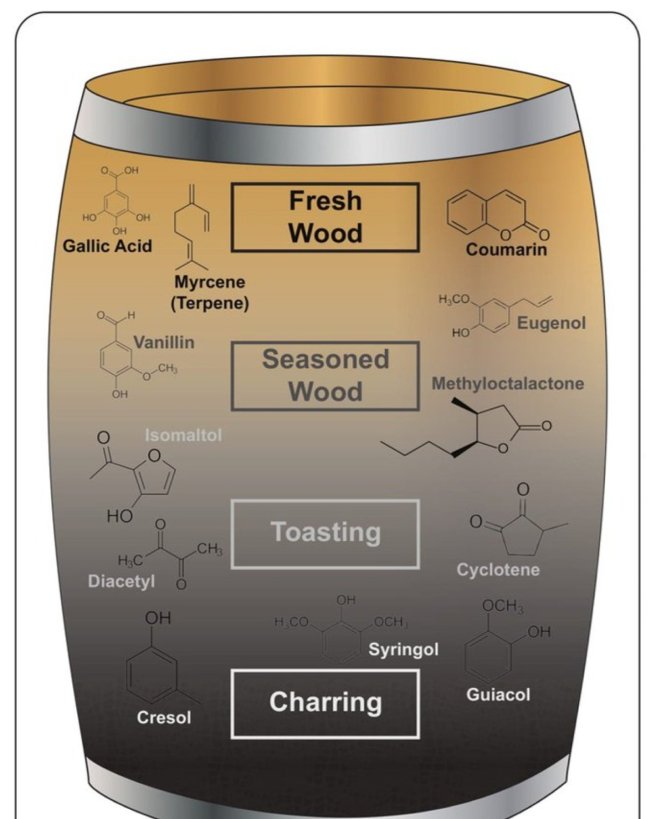

The second source of smoke in whisky comes from toasting a barrel. Toasting a barrel lightly alters the composition of the wood revealing new organic compounds, such as diacetyl, cyclotene, and isomatol. These can be viewed in the diagram below. In short, toasting the barrel releases these compounds, which releases a warmth into the whisky that would otherwise not be present.

Reference: https://talesofthecocktail.com/in-depth/influence-wood-flavor

The third source of smoke in whisky comes from a charred barrel. Quite simply, the burnt nature of the barrel releases “burnt” compounds into the whisky: cresol, guiacol and syringol as examples. See the barrel figure again, reference the bottom three chemical compounds as an example of how a charred barrel impacts the flavour and aroma of a whisky:

The fourth source of smoke in whisky is in the form of bio-organic waste products eminated from yeasts, sulphuric compounds released during the fermentation process:

https://vinepair.com/articles/glenkinchie-why-use-copper-stills

Sulfur has a unique scent, like that of rotten eggs, it’s iodine-like; however, don’t mistake sulfur for iodine. Women’s Whisky World’s exclusive blog has cited a scientific study, which shows that while present in whisky the concentration of iodine is insufficient to impact either a whisky’s flavor profile or aroma. See more about iodine in whisky here:

https://womenswhiskyworld.home.blog/2019/03/22/is-that-iodine-y/

Getting back to one of the byproducts of yeast during the fermentation process, sulphuric compounds are often picked-up in the copper stills during the distillation process, however Master Distillers can alter flow rate and choose the shape of a still so as to effect the outcome of a whisky’s flavour profile. For more information on this visit Women’s Whisky World’s exclusive blog site in the copper distillation process here:

https://womenswhiskyworld.home.blog/2019/03/30/still-shape-its-impact-on-whisky-flavour/

The next time you’re at a whisky gathering and someone comments on the smokiness of their whisky now you will know what they mean. Is it gentle or heavy peat flavour and aroma? Is it a meaty smoke from charring or a lighter smoke garnered from toasting, or could it be the more subtle medicinal undertones detected in whisky from the bio-organic sulfuric byproducts of the yeasts of fermentation? You won’t need to wonder anymore because now you know. Sláinte.

Yeast References for Further Reading:

https://scotchwhisky.com/magazine/ask-the-professor/15315/does-yeast-affect-the-flavour-of-whisky/

https://scotchwhisky.com/magazine/features/22834/is-yeast-whisky-s-new-frontier-of-flavour/